Welcome to the Post-pandemic Dream Home

Work “nooks,” sanitizer-stocked mudrooms, and other new features might soon appear in American houses—for those who can afford them.

Updated at 6:19 p.m. ET on February 9, 2021.

With all the additional time Americans are spending at home, the pandemic has made many people hyperaware of what they like—and what they don’t—about the space they live in: Natural light went from being a perk to a lifeline; an open-concept floor plan went from being an occasional annoyance to an exasperating privacy killer. Sometime hopefully not long from now, though, the threat of the pandemic will lift and homes will go back to being just one place among many where people spend a great deal of time. What will they have learned about what they want from their living space?

Recently, I consulted a dozen housing-industry experts as well as individual buyers and renters about how the design of homes—their size, features, layout, and location—might respond to pandemic-era needs, desires, and complaints in the next few years. COVID-19 could significantly accelerate two forces that were already on designers’ minds well before 2020: the rise of the home as a workspace, and a deeper emphasis on health and well-being.

For many Americans who are struggling financially during the pandemic, the question is not what they want in a home but whether they’ll get to keep their current one. “People’s housing choices are driven largely by how much they can afford to spend and proximity to their job,” Jenny Schuetz, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me. “Attributes like size, amenities, etc., come after that, especially for those on tight budgets.”

But among those who can afford to be selective, remote work has allowed some to sample their options. Last summer, Sara Sodine Parr, a 28-year-old tech worker, and her husband moved away from San Francisco and tested out a succession of monthlong rental houses in other cities, noting which features they liked and didn’t. At the end of the year, they bought a house in Austin, Texas, with three bedrooms (“so we can each have a separate office”), a front porch (“ideal for meeting neighbors”), and a garage (“we can turn [it] into a gym”).

Parr and her husband’s preferences—for more space, more closed-off space, and more outdoor space—are similar to what I heard from many others. “There’s no going back to a smaller apartment, if I can help it,” Gina Murrell, a university librarian in Oakland, California, who last year upgraded from a studio apartment to a one-bedroom, told me. Taylor Marr, an economist at the real-estate website Redfin, told me that in home-buying, “The new gold rush is square footage.”

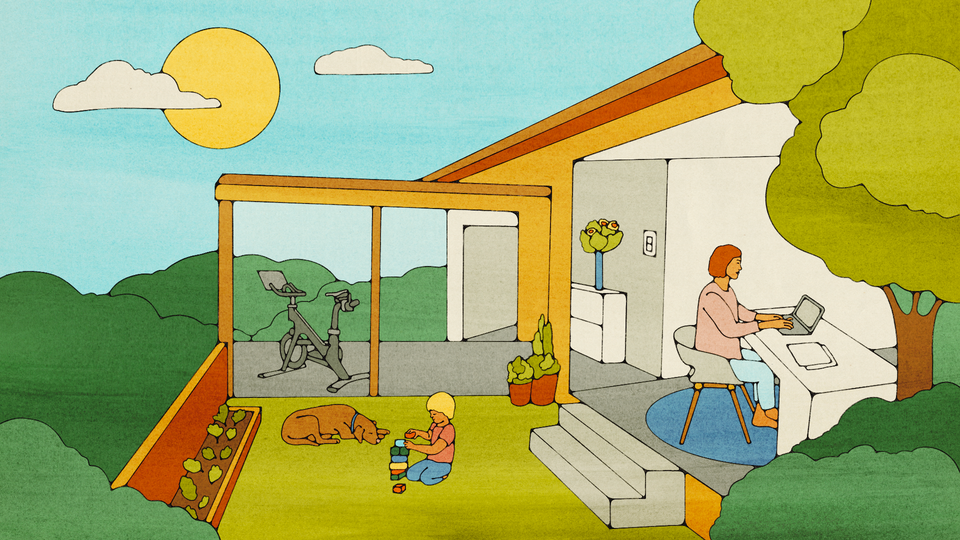

Square footage, that is, as well as ways of dividing it up. I heard industry experts talk about heightened demand for home offices, “Zoom rooms,” and outdoor sheds, as well as for more-compact “niches” or “alcoves.” In a recent presentation to homebuilders and developers, Mollie Carmichael of the housing-market research firm Zonda talked about “making use of the end of the hallway” or “tucking that space under the stairs” when adding a workstation to a floor plan—something, anything that isn’t the kitchen table or the couch.

As valuable as those setups would be, “It’s still going to be a luxury for someone to have a dedicated home office,” said Joel Sanders, a New York City–based architect who oversees MIXdesign, a consultancy that designs for people’s needs regardless of age, race, gender, or ability. At-home workspaces for everyone else lucky enough to have the option will have to be more space-efficient, and might rely on sliding partitions or “hidable” desks.

Of all the home-office innovation I heard about during my reporting, the apex was a remote-work bed that Sanders fantasizes about designing. He imagines that it would have “an ergonomic headboard that double[s] as a seat back,” “adjustable lighting,” “a waterproof work surface that swivels,” and “monitors with good sight lines for work, Zoom, and entertainment.”

Meanwhile, a parallel set of features and amenities is emerging to address health concerns, the other force that’s acting on people’s preferences. Carmichael, in her presentation, noted that nearly 70 percent of the homebuyers her company surveyed last year said they were willing to pay about $1,000 each for water and air filtration throughout a house. And Tim Anderson, the CEO of Focus, a luxury residential developer in Chicago, told me that in some projects, his company is installing features such as a heating system that has “all outside air coming in, so you’re not recirculating hallway air through your unit,” and touchless technology that would let people enter a building and then an elevator by scanning QR codes.

Jenni Lantz, a design researcher at John Burns Real Estate Consulting, told me she’s seen an increased interest in “transition spaces that provide a place to freshen up and drop stuff off before entering the home.” Similarly, Sanders remarked on the usefulness of a “post-pandemic mudroom” that might be stocked with sanitary wipes or masks and could allow “people with different forms of embodiment” to come home and clean not just their hands but also the contact points of a wheelchair, walker, or stroller. These sorts of accommodations don’t need to be high-end: One architecture firm working on an affordable-housing complex in Southern California is planning to install the units’ kitchen sinks close to their entryways, to facilitate easy hand-washing.

Another class of health-related enticements are the sorts of things that are especially beneficial during a pandemic, but also just nice to have in general. Some architects working on affordable-housing projects have planned pandemic-inspired features such as roof lounges, balconies, and community gardens. And Rose Quint, an economist at the National Association of Home Builders, a trade group, told me that, compared to two years prior, homebuyers in 2020 reported more interest in home gyms and neighborhoods with bike lanes and tennis courts. Industry analysts also mentioned yearnings for porches and private outdoor space.

The most imaginative of these ideas, from the Los Angeles–based design firm RIOS, is called a “super porch.” It’s “not a literal porch,” wrote Sebastian Salvadó, a creative director at RIOS, in a Wall Street Journal article, “but an enclosed space that covers a chunk of people’s front lawns.” He likened it to “a covered patio, with sliding glass walls and wood shutters to let you see out and let the neighbors see in.” In general, Salvadó told me, he’s seen “an increased use of front yards as social spaces” during the pandemic, and perhaps a neighborhood of super porches would coax more people out of their homes in the future.

Utopian (and expensive) home-design concepts like the super porch can be fun to fantasize about, but the pandemic has also drawn people’s attention to their home’s smaller annoyances. For example, Nicole Ursprung, an educator in Bratislava, Slovakia, quickly became irritated by the placement of electrical outlets in their apartment.* “When I’d try to work from the dining room table,” Ursprung wrote to me in an email, “I’d find that I had to plug my laptop into the nearest safe socket: almost behind the refrigerator, at chest level,” creating a horizontal obstacle they’d have to constantly limbo underneath. It’s a nuisance, but maybe it will be less frustrating once Ursprung is no longer spending so much time at home.

The pandemic has also changed many people’s preferences about where they want their home to be located. Schuetz, of Brookings, noted that if people in lower-income households are moving during this economic downturn, usually “it’s to find cheaper housing or in search of a new job.” But a more fortunate group of movers—those who expect to work remotely some or all of the time after the pandemic ends—might be able to optimize their comfort by changing their location.

According to search data from Redfin, city-to-city moving patterns haven’t changed much during the pandemic, with Americans continuing to leave expensive metropolitan areas (such as New York City and San Francisco) for relatively cheaper ones (such as Phoenix and Las Vegas). A more interesting trend is what’s happening within metro areas themselves. Many urban workers expect that they won’t have to go into the office as much in the future (if at all), which makes more-affordable but less-central locations newly viable. “If you only have to [commute] twice a week, a 90-minute drive is less of an issue than if you have to do it every day,” said Issi Romem, the founder of MetroSight, an economic consultancy.

But living outside a city does mean giving up some of the things that make cities enticing. “If I was a thirtysomething with two kids and I was used to going to cool restaurants, cool things to do … I think they still want that—they don’t want to go to chain restaurants,” said Tim Anderson, the developer.

To address this problem, Anderson told me, two suburban apartment developments his company is working on will have restaurants, bars, and shops on the ground floor. “The integration of retail with the residential is critical to mimic the urban experience,” he said. (One consultant I heard from used the ungainly term surban to refer to these city-like environments in suburban areas.) Many fancy apartment buildings in cities across the country have had high vacancy rates during the pandemic, but Anderson expects demand for city living to come back in Chicago in another year or two.

Perhaps a stronger draw than work and cool bars is the opportunity to live near loved ones. One married couple I spoke with, Dustin Hiatt and Susan Pratt, moved from South Carolina to Iowa early on in the pandemic for Hiatt’s job, but then, once he was permitted to work from home indefinitely, moved again to Nebraska, near members of Hiatt’s family. The rise of remote work could lead people to flock to places with cheaper housing and beautiful landscapes—say, Boise, or Bend, Oregon. But “the odds of ending up where your parents are, where your siblings are,” Romem said, seem “better than some random place, all else equal.”

When contemplating the post-pandemic home, it’s hard to say which features will be fads and which will become fixtures. But after a year-plus of people simultaneously scrutinizing their living spaces, their desires—and the housing industry’s offerings—are likely to change in noticeable ways.

None of the people I spoke with said they expect office work to uniformly return to what it was before the pandemic, with workers commuting five days a week. Even if many companies do order their employees back, there will likely at the very least be a wider understanding of the home as a place where many people get work done, instead of or in addition to an office.

Hygiene practices, in contrast, seem more likely to revert to pre-pandemic norms. As important as air filtration or touchless entry might feel now, they might seem a lot less so once the threat of the coronavirus dissipates. As I wrote last year, people probably will abandon constant hand-washing and other onerous sanitary practices once they feel they’re no longer necessary.

So for the fortunate minority who can afford it, the mid-2020s dream home seems less likely to have a post-pandemic mudroom than to have a Zoom room. It might also be big and relatively secluded—but not so remote that some simulacrum of urban life isn’t nearby. With luck, even those in more-modest homes will benefit from more integration with the outdoors and from space-efficient designs that allow for working comfortably. The luckiest of all might even find themselves taking calls in their work-from-home bed.

* This article has been updated to use Ursprung’s preferred pronouns.