What We Lack in Real Estate: The Spirit of Curiosity

Josh Panknin

Guest post by Josh Panknin, Director of Real Estate Technology Initiatives in the Engineering school, Columbia University

Late on the night of August 6, 2012, engineers in the control room at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, CA anxiously awaited word from a rover named Curiosity. Curiosity was about to enter the seven-minute-long final phase of a frigid 350-million-mile, nine-month journey to Mars to begin its mission of finding out if life does, or ever did, exist on the red planet. This final phase, what would turn out to be one of the most complex and technologically advanced achievements of the space program, was not-so-affectionately known as the “7 Minutes of Terror.”

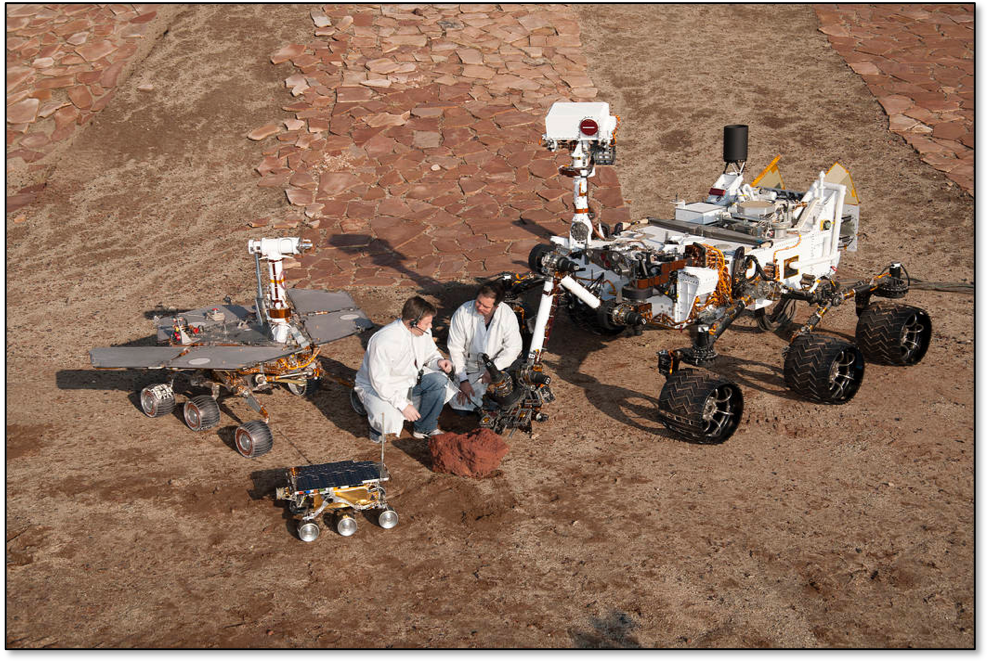

Curiosity was unique. It was the largest (about the size of a MINI Cooper) and most advanced rover ever sent to Mars, weighing almost 2,000 pounds and packed with sensitive scientific equipment. In comparison, the previous two Mars rovers weighed 23 pounds (Sojourner) and 400 pounds (Spirit and Opportunity). The sheer size of Curiosity forced NASA and JPL to completely redesign how to get it through the atmosphere of Mars and safely deliver it to the surface. This task was placed in the hands of a special group at JPL known as the Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) team.

Source: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

The landing sequence is discussed in detail in the book The Right Kind of Crazy by Adam Steltzner, lead engineer for the EDL phase of Curiosity. It’s a great read and highly recommended. And while sending a rover to Mars has nothing directly to do with real estate, Curiosity is a vivid illustration of the ability of humans to create astonishingly complex feats of engineering and the leaps in capabilities that technology has provided to the world. What was striking to me as I read Steltzner’s book and reflected on the Curiosity program is how far behind in technological sophistication the real estate industry seems to be in comparison to the advancements in other industries such as medicine, aerospace, and even technology itself. Far, far more complex technology exists than what we have in this industry and we are nowhere close to reaching those limits of technology. The existence of technology, or the ability to build the kind of technology sophisticated enough to address our challenges more effectively, is not the problem for real estate.

The problem, rather, is in our approach to innovation. It’s in our approach to creativity. It’s in our willingness to explore and put resources into discovering and developing solutions that could offer enormous potential to this industry and to the transformative effect that potential could have on our world. This is one of the few, if not the only, industries that can quite literally change our world. We can change the way our world looks, how it operates, how it uses energy. We can provide or contribute to solutions to major issues such as lack of housing in third-world countries or sustainable communities. We can not only create better businesses, we can create a better world.

Creativity and innovation are not qualities that were lacking for the Curiosity team. JPL, with the motto, “Dare Mighty Things,” is well-known for its exploration of new ideas and pushing the limits of their own capabilities. Nor was there any shortage of funding and support for that exploration. Funding to create teams with broad capabilities and deep expertise in each of the needed capabilities. NASA and JPL know very well the difficulties and risks associated with pushing the limits of our capabilities and they’re willing to provide an environment, in both mentality and financial resources, that support the kind of exploration that leads to true innovation. The real estate industry, however, has not, thus far, been willing to support innovation moonshots that could completely transform this industry as we know it.

We’ve instead put resources into pursuing incremental improvements to systems and capabilities that we already have. We often fund hockey-stick subscription revenue projections (of which many are unrealistic) rather than foundational technology development. Much of the technology that has been produced for the real estate industry is simply taking capabilities that are possible by using Excel spreadsheets and creating a web-based platform to perform the same tasks, something I refer to as “webitizing” tasks. Granted, there are some companies who are using the web to make connections among people that would not otherwise be possible and some who have made processes more efficient, but most are not pushing beyond the limits of our current capabilities for anything truly transformative. We’ve opted for easy, fast, and cheap. We’ve stuck with what we know.

Low risk + low time + low cost = low results

Nobel Laureate George Smoot (Physics – 2006) made this point much more eloquently and succinctly than I can when he said, "People cannot foresee the future well enough to predict what's going to develop from basic research. If we only did applied research, we would still be making better spears."

What is Complexity?

As Curiosity entered the atmosphere of Mars it employed a series of maneuvers including guided entry at 13,000 miles per hour facing temperatures reaching up to 2,100 degrees Celsius, the deployment of a 100-pound parachute that had to endure 65,000 pounds of force to slow the rover, followed by a radar-guided, jet-propelled descent-vehicle, and finally a technique called the “Sky Crane” requiring the descent-vehicle to slowly lower the vehicle to the surface on a series of cables without damaging the rover or any of the equipment on board.

While taking only seven minutes, EDL slowed the rover from 13,000 mph to 1.7 mph. The process required six separate vehicle configurations, over 500,000 lines of code, 76 pyrotechnic devices, ropes, knives, and the largest supersonic parachute ever built. And it was 100% controlled by a computer with zero human intervention. The sequence had to work in exactly the right way at exactly the right time or the entire $2.5 billion, eight-year mission would have been a complete failure with Curiosity ending up lost as a twisted mess in a smoking hole somewhere on the surface of Mars.

But at 10:32pm Pacific Time, Curiosity landed successfully and began to quietly settle onto the desolate surface of Mars just 1.5 miles from its intended target. In case you want to do the math, after a 350-million-mile journey, that’s a margin of error of 4 billionths of one percent.

To give you a better idea of the complexity and challenges that went into the landing, here’s a video. I’ve watched this about 75 times and it still hasn’t gotten old.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ki_Af_o9Q9s[/embed]

I’d like you, for a minute, to think about the complexity of the Curiosity mission. I’d like you to think about how difficult it is to send a 2,000-pound, $2.5 billion spacecraft 350-million-miles from earth and land in a narrowly defined area with a plethora of scientific instruments and thousands upon thousands of components that must function together seamlessly at exactly the right time in exactly the right way. The amount of engineering, design, software and hardware development, and planning that went into the Curiosity mission is absolutely mind-boggling, even more so that it all worked as intended.

Despite this complexity, the fact is that we, as humans, were capable of creating what was necessary to launch, fly, land, and operate a rover on the surface of another planet in our solar system. Now think, for another minute, how much more complex a project like Curiosity is compared to creating a better leasing management system or valuation model for the real estate world. It is, in comparison, infinitely more complex. And there are hundreds of other examples of complex technological achievements in other industries/organizations that could be used to drive this home.

To be clear, I don’t think the real estate industry is broken. It continues to operate much the same way as it always has. The problem with this is that real estate continues to operate…. much the same way it always has. Over the hundred years or so of the modern real estate industry, we’ve refined processes almost as much as they can be refined using traditional methods. The industry had a wave of technology tools come along in the form of Microsoft Excel, Costar, Argus, and a few others that made the existing functions a little easier to use and offered a few capabilities that were just too cumbersome to perform prior to their existence. A few larger companies have taken steps in the right direction with funding and teams, but I don’t think even those steps have gone far enough, and they are certainly the exception rather than the norm. So yes, it has changed, but when you consider the pace of advancement in real estate compared to some other industries, it becomes very clear how far we’ve fallen behind in improving our capabilities.

Like the majority of industries, technology will drive most, if not all, of the advancements we can possibly achieve in the real estate industry, whether it’s the writing of software, the collection of data, the development of new materials for construction, or the optimization of real estate development, construction, management, valuation, lending, etc. Most likely it will be applications to developing software or hardware or materials that I can’t even think of.

The Suit that Doesn’t Fit

I’ve heard many reasons for the lack of progress in real estate. I often hear that people in the real estate industry are “technophobes” incapable or unwilling to adopt technology like other industries have done. Yet I don’t know one single person in real estate who would resist a piece of technology if it helped them do their job better. I hear that those in power are resistant to change because it will take away their competitive advantage. I don’t believe that is completely true. I’ve also heard that real estate just isn’t all that complicated and doesn’t need technology. I do think this is true. Real estate doesn’t NEED technology to continue to operate as it currently does, but real estate does need to employ technology to get better.

So I don’t think the industry is resistant to technology. What I see instead is technology that doesn’t really work as it should. It doesn’t quite fit. It checks the boxes for what it should do according to textbook definitions, but it doesn’t entirely capture the functionality or the intuitive way that real estate professionals do their jobs. The way I often describe it is to imagine that you’re looking for a new suit. You’d like a dark blue suit with a specific fabric and a specific style. You go to the store, find the rack with the suit you’re looking for, pick up a jacket and try it on. But that jacket is four sizes too big. What do you do? You take it off and put it back on the rack. Even though it’s very close to what you’re looking for, it doesn’t quite fit and won’t do the job you need it to. I see this time and time and time again in real estate technology. It kind of checks the boxes, but won’t do the job as well as the users need it to.

On one hand, much of the technology being introduced to the real estate industry is developed by people who don’t have a real estate background and don’t understand the intuitive way that real estate professionals make decisions. On the other hand, real estate professionals don’t understand technology well enough to clearly articulate what they need. Those with a technology background often think real estate is easy and those with a real estate background often think technology is easy. Expectations thus become unrealistic on both sides (I discuss this further in the section below on the Communication Gap idea).

In addition to this lack of crossover knowledge, I think there are four other major reasons why technology has had a difficult time penetrating the real estate industry. First, real estate has tremendously low data consistency, capture, and quality, especially for the level of quality needed to run advanced data analytics. Second, the heterogeneity of real estate makes it very difficult to build standardized systems. Every city, property type, individual property, lease, expense item, etc. is unique. It’s easy to build individual Excel spreadsheets for each unique property, but immensely more difficult to build technology that allows this variability to be captured effectively by each individual user. Most technology introduced to real estate doesn’t allow the nuanced flexibility needed in practice. Third, most technology in real estate addresses an extremely narrow aspect of the decision-making process. Firms are required to subscribe to multiple, sometimes dozens, of different technology providers to achieve decent coverage of the decision-making process. Many times, these multiple technologies aren’t compatible and the process can’t flow seamlessly, creating a different kind of headache for firms and reducing a firms’ willingness to adopt a single technology that doesn’t provide significant improvement of their operations. Fourth, most “solutions” being offered are surface-level, incremental improvements to tasks rather than foundational changes to operations.

Role Models

While real estate is not as complex or complex in the same way as sending a rover to Mars, it is nonetheless complex in its own way. Aerospace and technology are largely governed by the laws of physics. Medicine is a blend of art and science, where it is still not wholly understood as to why one person reacts differently to a treatment than another. Real estate, in contrast, is a mix of quantitative and qualitative data and is largely a human-driven industry. A large proportion of inputs that go into any decision in real estate are qualitative and can only be quantified using a potential range of values (range of potential rents, etc.) that are themselves subjective. It’s affected by both macro and micro influences, by an intricate network of connected factors that are all relative to another in a form of dynamic complexity that is difficult to define, much less understand and automate.

Given these challenges, given the scale and nature of the industry itself, how do we do better than we have? How do we more effectively tackle problems and potential? How do we put the right kinds of teams in place with the right kinds of resources to achieve these goals? As previously mentioned, we don’t really have any examples of real estate organizations who have been extremely innovative or who have had a significant impact on the market through technology. If we can’t find examples of where we want to be within our own industry, we must look outside of it.

Much of my recent research has revolved around organizations such as DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), JPL (Jet Propulsion Lab), Skunk Works (the R&D division of aerospace giant Lockheed Martin), Bell Labs (the R&D division of AT&T), and Xerox PARC (the R&D division of Xerox).

You may not be familiar with some of these organizations, but I guarantee you’re familiar with many of their achievements. While certainly not an exhaustive list, some of the more well-known achievements are mentioned below:

- DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency): Played major roles in the development of the Internet (ARPANet), GPS, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence.

- JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory): Developed the first satellites and recently leading Mars rover exploration programs.

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration): Led the space program, successfully landed men on the moon, etc.

- Skunk Works (R&D division of Lockheed Martin):Developed advanced spy aircraft and the currently used stealth aircraft.

- Bell Labs: Awarded eight Nobel Prizes for research; developed cell phone technology, lasers, solar cells, communication satellites, and the Unix operating system.

- Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Corporation): The first personal computer, laser printer, computer mouse, and graphical interface. PARC has created $1 trillion in new industries, $60 billion in startups and spin-offs, and almost 6,000 patents and patent applications.

Think about how what those organizations developed affect your daily life. How much do we rely on our cell phones, the internet, computers, etc.? How many peripheral technologies came out of the research and development pursued by those organizations? Quite a lot.

One thing I began to notice as I read story after story about the products and capabilities that these organizations developed was that even though they all produced something different, they all took almost the exact same approach to innovation. They all hired some of the absolute best people in their fields to build teams with broad sets of expertise and created immense breadth and depth in capabilities and skills. They paid them above market rates. They gave them time to be creative, experiment, and even fail. They put resources, both financial and human into these endeavors and they paid off enormously. In many cases, they reached achievements that were written about as science fiction only decades before.

Are these organizations just special and capable of things most companies aren’t? Well, to an extent, yes. Because what they didn’t do is try to do too much with too little. They provided teams and resources at a level necessary to meet the challenge. A large majority of startups today have a handful of people, a few hundred thousand dollars, and maybe 12 months to get to revenue before they run out of financial runway and must shut down. What is the likelihood that a handful of people with a limited budget and a short period of time are going to develop effective solutions to complex problems like the ones we face in this industry? It’s not that it can’t or won’t be done, but it’ll be the rare exception with extremely high failure rates while the organizations I mentioned above have and will continue to experience much, much greater rates of success on projects that are much more impactful.

If we have clear models of what works for innovation (DARPA, NASA, etc.) and what doesn’t (the startup world with a failure rate in excess of 90%, by some estimates), why do we keep approaching problems with the same mindset that has proven to fail an overwhelming majority of the time. Would the immense resources put into the six- or seven-thousand individual “proptech” startups not be better used to fund a smaller number of companies with greater capabilities? Or would it be more effective to recognize that there is much greater potential to be achieved if we approach the creation of teams/organizations differently from their inception rather than waiting years until they reach a certain level of revenue?

In an upcoming series of papers that I’ll be writing jointly with the University of Oxford’s Andrew Baum and Andy Saul, we’ll explore in much more detail some of the pathways to getting better as an industry. This includes better models and approaches for startups wishing to create a new product or capability, for corporations who are the existing dominant players within a given niche, and investors who are providing the funding for many of these ventures to get underway at their early stages. Our goal is to provide bridges for the real estate industry to use to make the development of new technologies less risky, less costly/less wasteful, and more valuable for everyone involved. I would, however, like to touch on a few of those here and then expand on them in the upcoming papers.

Communication Gap

One of the reasons broad teams with deep capabilities perform so well (when structured correctly) is that broad teams bridge knowledge from one end of the spectrum to the other, helping to keep communication and expectations clear across all the different skill sets that are needed.

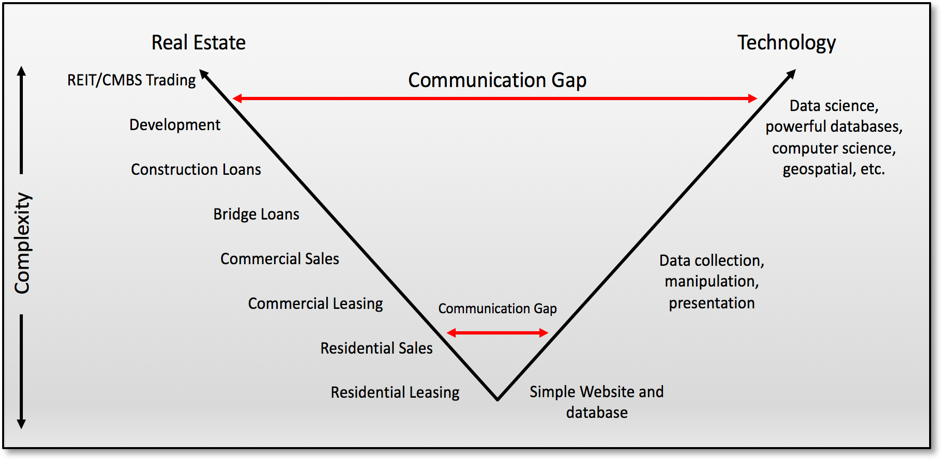

Technology is only valuable when it’s effectively applied to a domain, whether that domain represents a problem in society, a business, or something else. The challenge comes in maintaining clear communication across those with deep domain knowledge and those with deep technology knowledge. In most applications, as the complexity of the activity in a domain increases, the challenge of capturing that complexity in code becomes more and more difficult. The languages of real estate and software are vastly different and can lead to miscommunications that can prove to be fatal to a project. I call this the Communication Gap, as illustrated in the figure below (the real estate activities are subjective and for example only, not meant to be a formal ranking of difficulty).

Essentially, as the complexity of the activity within real estate increases, the level of technology capabilities you need in order to effectively capture that complexity with code increases proportionately. I know from my own personal experience, and I’ve heard from numerous others in both the real estate industry and the technology industry, that this communication gap is a major impediment to developing more sophisticated and advanced technologies.

As niches such as residential leasing applications or home loan automation are effectively addressed and the number of companies competing for that market increases drastically, the next generation of real estate technology must begin to tackle a new set of problems. These new problems are usually more complicated than the old ones and require a new approach. They require more resources, both financial and human, and more willingness to allow for exploration and even failure. Teams must become more robust and begin to tackle issues that are broader and more difficult. In order for that to happen, we must form and fund teams that are more robust in both breadth and depth.

When we set out to build a single-family house, we go through a certain process of design and then gather the necessary resources and team. We’ll need an architect, a general contractor, some subcontractors for various activities such as electrical, plumbing, roofing, etc. We’ll also need the materials, most likely lumber, sheetrock, and maybe some brick for the exterior. Let’s say we’ll need twenty people to build this house.

However, when we set out to build a new high-rise we instinctively know that the team we’ll need will be larger, with a broader set of capabilities, and different sets of materials. We’ll need not an architect, but a team of architects, designers, engineers, etc. We’ll need hundreds of construction workers. We’ll need components (elevators, lobbies, loading docks) that we wouldn’t need at all in the single-family house. And when we set out to build this more complex high-rise we have zero problem allocating the resources necessary to accomplish the task.

In real estate, we work with data, we work with financial applications, we work with markets, and, because real estate is physical, we work with geospatial factors, among many others. To build extremely sophisticated and broadly integrated technology, you’ll need not only a data scientist, but at least one that specializes in collecting data, one in analyzing data for insights, one in visualizing data, etc. This specialization is needed across the different functionality an application will need.

Yet so far, we’ve expected the high-rise (transformative tech) to be built by the team building the single-family home. This scaling of team and capabilities holds across industries and countries and is not unique to real estate. We must acknowledge and start allowing for better foundational resources from the start if we want to push the abilities of technology.

The Players

It ultimately takes people to make change happen. In 2017 there was roughly $12.6 billion of funding to real estate tech related companies, up from around $221 million in 2012. The increased attention, resources, and momentum are great, but I don’t think these resources are being used effectively. Out of the $12.6 billion in 2017, about $5.2 billion went to the top ten deals of the year. The remaining $7.4 billion was split among what is estimated to be somewhere close to 7,500 “startups” in the real estate tech niche.

The three broad categories I’ve defined as the “players” in real estate tech are the startups, the corporates, and the investors. Below I briefly explain my opinion on why each of these groups faces challenges in successfully developing the kinds of technology that will prove to be transformative. Again, this is a very high-level overview and these are topics that will be addressed in much more detail in future papers.

I want to note here and make it extremely clear that none of the criticisms/critiques below are personal towards any of the people involved. This is an extremely difficult industry to jump into and I have tremendous respect for the people who have had the guts to throw their hats in the ring and try to make things happen, many of whom I know personally and deeply respect. Fortunately, because of them, we have lessons to learn on how we can improve as an industry.

Startups

Lack of Resources

The average early-stage “startup” consists of a handful of people and a few hundred thousand dollars that will get them maybe twelve months of runway before they must either begin generating revenue, raise more funds, or run out of financial runway and shut down. As touched upon previously, now that the relatively simplistic parts of real estate (leasing, home loans, etc.) are addressed, we must begin to move towards the more difficult challenges. As the challenges become more complex, the teams must also, as I discussed above with the Communication Gap. However, it seems that the composition of teams is not changing at the same pace as the complexity of the challenges being addressed and, as a result, solutions to these more complex challenges are largely not effective.

Domain Knowledge

“Every science that has thriven has thriven upon its own symbols.”

– Augustus de Morgan (1864)

Another major issue I see with many early-stage real estate tech startups is a lack of real estate experience. Many early-stage companies are comprised of individuals who have either a very strong technology background or a background in some other industry, but lack deep, or sometimes any, experience in the real estate industry. Domain knowledge is crucial in any industry and real estate is no exception. In fact, one could argue it’s more important in real estate than many other industries because of the proportion of qualitative data that goes into the decision-making process.

This lack of domain knowledge often leads to a perception that real estate is “easy” (it’s not) and to an oversimplified approach to solving the problem. What you end up with is something that sounds good, but doesn’t quite work in the real world. Many of these early companies eventually realize the complexity associated with real estate and try to pivot, but they’re not always successful. Without domain knowledge in the industry in general or the specific niche the startup is addressing, it’s almost impossible to capture the solution effectively.

Corporations

While startups generally have the willingness to try new things, they typically don’t have the resources. Corporations, on the other hand, generally have the resources, but don’t have the willingness to pursue long-term, risky research and development (R&D). Many are confined by the earnings cycle and are handcuffed by the quarterly results that support stock prices. Others are hesitant to disrupt an otherwise steady flow of income to support major expenditures in what is seen as a risky attempt to increase capabilities.

Another major obstacle for large, established companies is the sheer number of startups that vie for adoption. It’s not uncommon to hear from professionals in established companies that they receive dozens of calls per week from companies trying to push their new software. Many of these companies don’t have fully working products and are so similar to other startups that have contacted them that they don’t have any clue which company to support. Just like having too many items on a menu, some of these larger corporations are too overwhelmed to make decisions.

Finally, something that has become widespread is the claim of real estate technology providers using advanced technologies such as “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “deep learning,” etc. For many reasons, I think these claims are extremely overhyped compared to the reality of the impact on real estate analysis or decision-making. A recent headline in the MIT Technology Review based on research done by an investment firm in London titled, “About 40% of Europe’s ‘AI companies’ don’t use any AI at all” is a clear warning to firms to vet any claims about technology capabilities. The inclusion of these technologies in marketing and fundraising materials can lead to more attention and funding (15% more, on average, according to the article), but don’t always match reality.

Technology Knowledge

In contrast to the lack of domain knowledge that startups often lack, corporations are typically extremely deep in domain knowledge, but short on technology development knowledge. This lack of technical knowledge often leads to unrealistic expectations of the amount of resources and the time-frame needed for the development of effective technology.

Building, testing, and implementing technology for complex financial and real estate functions takes time and takes resources, both human and financial. The big payoff that technology has the potential to deliver simply will not happen if the resources given to the project are not sufficient.

Investors

Investors and venture capitalists (VC’s) are stuck somewhere in the middle. They try to pick the best company to back and, in the case of VC’s, must also attempt to keep their limited partners happy by not taking risks that are too big while also maximizing returns. This combination makes it difficult to support the kinds of risky investments that could turn out to completely change the industry.

But investors should also beware not to reward claims of advanced technologies or “quick and easy” solutions that sound great, but aren’t always grounded in the realities of the industry.

The Academic Advantage

Finally, I’d like to discuss something that isn’t traditional for the real estate industry – strong partnerships with academic institutions. For decades, other industries have had close working relationships with universities for several reasons. One, universities supply a constant stream of highly educated, skilled workers to the workforce. Second, universities, by their nature, focus on foundational research to develop new, novel, and cutting-edge solutions to tomorrow’s problems, something that industries have found extremely valuable to their competitive position in the market.

The university-industry partnership model is not new, but it is new to the real estate industry. If done properly, I believe it can be enormously valuable to all participants. “A study conducted by Steven Brint, distinguished professor of sociology and public policy at the University of California, Riverside, found that universities contributed to almost three-quarters of the world’s most groundbreaking inventions (74 per cent) and were the most important or a very important actor in four in 10 cases.

Because foundational research is so challenging, the power of industry and academia joining forces to develop practical and implementable advanced solutions to current challenges could provide a significant boost to technology’s role in the real estate industry.

Why Innovate?

I have to thank my friend, Professor Andrew Baum from the University of Oxford Saïd Business School, for this section. I think it may be the most important part of this paper. After reading a draft of this paper, he not so bluntly asked me a simple question, “Why do we need innovation in this industry?” It’s one thing to talk about innovating, but given the challenges and sacrifices associated with true innovation, why should we put ourselves through the pain and risk of the innovation process?

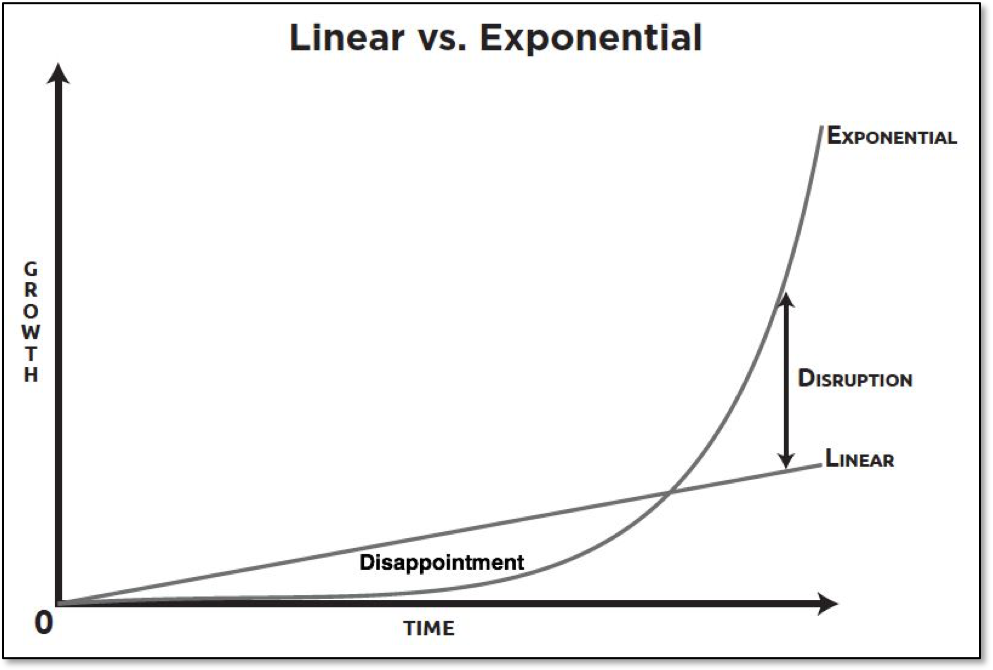

The figure below shows a concept that compares two types of improvements companies can pursue: linear vs. exponential. Linear improvements focus on small, quickly delivered improvements to keep up with the competition, which is usually exactly what the competition is doing to keep up with you. To achieve exponential improvement, however, there’s a period where a firm might fall behind the competition (assuming no changes in personnel or funding for research and development of new capabilities). Often when a firm finds themselves falling behind in the short-term, they panic and decide to pull back from exponential improvements and again begin to pursue linear improvements to keep up with the competition in the short-term. But those that stick with pursuing exponential improvements over the long-term often see their competitive position in an industry improve dramatically.

Source: Exponential Organizations by Ismail, Malone, van Geest, and Diamandis (2014)

Source: Exponential Organizations by Ismail, Malone, van Geest, and Diamandis (2014)

Recent research suggests that companies that focus on innovation report up to 22% higher profit margins and those in the top quartile of their respective industries have innovation orientation scores up to 22% higher than companies in the bottom quartile of their industries. There’s also the fact that people are what drive innovation and the best way to attract the best people is to offer an environment where they can be creative and contribute to the growth of the firm in meaningful ways.

All that is great and very logical, but it’s not what will drive most people to the late nights, the frustration, the risk, and the sacrifice. More importantly, I think many of us see a huge potential in this industry and have an inherent, deeply personal desire to be the ones that fulfill that potential. Almost every single person I’ve met in this industry initially talks about business and revenue and some type of tool that will help them do their job better. But after getting to know them, they start talking about their desire to do something good. To do something that makes an impact. Whether that motivation revolves around children, animals, the environment, gender issues, education, or something else, everyone that I’ve worked closely with has a cause that they see being positively affected by and through this industry. It’s this passion that drives them and it’s been my pleasure to work with that kind of people.

Conclusion

While many of these topics could be (and will be) the topics of entire papers, my goal was to provide a high-level overview of the obstacles we face in advancing the potential of technology in the real estate industry and to hopefully make the point that developing the kind of technology that can have a major impact on this industry is well within our grasp. The barrier to accomplishing this is not technology itself, but rather our approach to developing and implementing technology on a large scale.

“Easy reading is damned hard writing.”

– Maya Angelou

“…the key is we don't stop until that technology can't be seen. It should be invisible…”

– Lisa Girolami, Director, Walt Disney Imagineering

Maya Angelou is certainly correct about writing, but I think that also applies to anything that’s worth doing, including real estate tech. And to make that technology good enough that it’s invisible, it won’t be easy. But with a shift in mindset and a willingness to sponsor impactful research, deep and broad teams, and an environment of creativity, experimentation, and sometimes failure, I have no doubt this industry could look vastly different in five or ten years than it does today.

About The Author:

Josh Panknin is the Director of Real Estate Technology Initiatives in the Engineering school (Industrial Engineering and Operations Research) at Columbia University and a Visiting Assistant Professor of Real Estate at New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate. His focus is on developing new capabilities for the real estate industry through technology. By leveraging the immense technology resources at Columbia Engineering, he focuses on foundational research that combines broad and deep engineering capabilities for more holistic solutions rather than narrow, incremental improvements.

Prior to academics, Josh was Head of Credit Modeling and Analytics at Deutsche Bank’s secondary CMBS trading desk where he helped develop and implement automated models for valuing CMBS loans and bonds. He also spent time at the Ackman-Ziff Real Estate Group and in various other roles in research, acquisitions, and redevelopment. Josh has a master’s degree in finance from San Diego State University and a master’s degree in real estate finance from New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate.